Autobiographies of mid-century famous biologists (e.g. What Mad Pursuit [1], Embryologist: My Eight Decades In Developmental Biology [2]) offer nostalgia distillates: fairy tale-like scientific quests involving lots of witty correspondence, endless conversations on the grass of an Ivy League Institution, and pub crawling with colleagues to unveil the mysteries of life. When not so many people were “professional scientists” – for obvious reasons such as lack of democratization in higher education access or inexistent scientific collectives – experimental science was comparable to sophisticated craftsmanship.

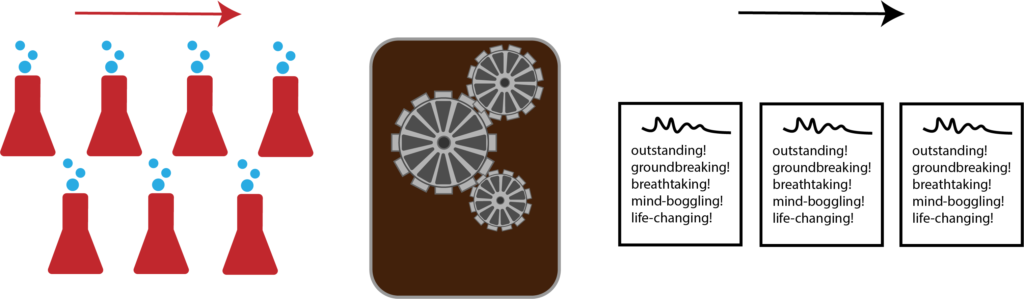

Academia is now a global system of mass production mirroring the reality of the larger outer world, a microcosm where productivity requirements and competitiveness have been transposed from the ultra-liberal capitalist sphere. Knowledge is the product of this system and scientific publications guarantee its face value. Picking a research direction turns into a delicate trade-off between natural curiosity and pragmatism regarding the publishing context (funding, competitors and target journal). These logics have nurtured a whole ecosystem of jobs aiming at optimizing the scientific production, from the grant-writer to the scientific editor. Almost-there trends include the development of market studies prior to research programs establishment, and research strategy consulting for academics.

Inside the academic lab itself, human labour remains heterogeneous: there is unqualified labour (research interns who perform cheap or time-consuming labour in exchange for professional experience and skills), highly-specialized labour (career research assistants with a very specific domain of expertise), highly-qualified labour (postdoctoral researchers and research associates with a spectrum of activities going from experiment conceptualization to data production) and highly-evolving labour (graduate students who start at the bottom, perform cheap labour in exchange for skills and end up qualifying as postdoctoral researchers with an upper-hand on the conceptualization of experiments).

The structure of this workforce, especially in experimental biology, is challenged by increasing robotization in areas where theoretical predictive power is limited and screening of multiple components used to isolate new functions or promising compounds. In these fields, organization of fundamental science phenocopies strategies in clinical research and biotechnologies. Prominent examples of ongoing robotization of bench work include the NYSCF Global Stem Cell Array to derive automatically induced pluripotent stem cell lines from patient biopsies and cloud lab initiatives in which experiments can be outsourced on robotized equipment with additional support from technicians (similar to Amazon warehouses functionment). Stereotyped experiments that are modular (genetic modification, clone isolation, genotyping, characterization and then drug screening) do not require anymore human operators. There are positive aspects in this trend, such as the enhancement of reproducibility. Negative outcomes would be erosion in the experimental training of young scientists and standardisation of experimental procedures, ultimately leading to technological and funding races instead of producing new experimental and (hopefully) clever designs

A large segment of research focuses on the integration between academic work, economic and innovative growth [3-6] to accelerate the development of our societies. There is no question that modern science was powerful and efficient in addressing some of the modern challenges threatening human societies, such as the fast development of vaccines to fight emerging infectious diseases. However, if innovations that lengthen human lifespan are heavily publicized, the current economical model of academic research performs poorly in what could be called sustainable innovation [7].

It is established that our current economic model does not support sustainable growth and that no profit-driven logics can help to preserve human and non-human species, together, on a habitable earth. Industries are consciously green-washing their products to advertise an easy and superficial transition, but academia does little at promoting frugality, aside from isolated models of citizen science [8,9]. While fordizing, we have forgotten three important consequences of this ideology:

- Academic power concentrates in the hands of those who own the capital – the wealthiest nations that have already heavily invested in new technologies – excluding other countries from participating in future scientific discoveries.

- Academic labs are seen as economic units of production rather than training modules. Yet, the partial failures of our modern educational system show that masses cannot be trained with uniform programs [10]. Research units can train diverse scientific citizens, armed to address the challenges human societies are facing in the coming years.

- Monopolistic industries emerge and reinforce scientific uniformity, ultimately dictating research trends.

The scientific ideal involves curiosity and independent thinking. Researchers question established truths with reasonable doubt. It seems now naive to dissociate social reforms from economic ones – should we imagine new economic models of academic research?

[1] What Mad Pursuit: A Personal View of Scientific Discovery, Francis Crick, Basic Books (1990)

[2] Embryologist: My Eight Decades In Developmental Biology, John Trinkaus, J & S Pub Co (2003)

[3] Technology and the Pursuit of Economic Growth, David C. Mowery and Nathan Rosenberg

[4] https://academic.oup.com/icc/article-abstract/19/2/465/719674

[5] https://academic.oup.com/ser/article-abstract/6/2/283/1700410

[6] https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/gec3.12463

[7] Christian Le Bas, « Frugal innovation, sustainable innovation, reverse innovation: why do they look alike? Why are they different? », Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 2016/3 (n°21), p. 9-26.

[8] Bhamla, M., Benson, B., Chai, C. et al. Hand-powered ultralow-cost paper centrifuge. Nat Biomed Eng 1, 0009 (2017).

[9] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/04/frugal-design-medical-innovations-communities-pandemic-covid19/

[10] Towards Personalized Content in Massive Open Online Courses, N. El Mawas, J-M. Gilliot, S. Garlatti, R. Euler and S. Pascual, {https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01770041},